Dear Resourceress,

One of the hardest things about being a new leader is facing all the mistakes I make. Especially those mistakes where I’ve hurt someone else, and I know I could have done a better job if I just had more time to plan and consider my response. Part of the learning curve in my new job is that my to do list just comes at me way too fast.

When I make a mistake and then hurt someone on top of my already growing responsibilities, my workload only increases. My mistakes start to weigh on me. I’m finding more tentative the next day, more indecisive, questioning my judgment. I start to feel like an imposter.

Do I just have to perfect my leader skills so I never make any mistakes, ever? Or … ?

Signed,

Who Has Time to Get Perfect?

Dear No Need to Perfect,

As a recovering perfectionist, I’ve been learning that mistakes are part of life, and definitely part of leadership.

Rather than striving for perfectionism (which is a tool of white supremacy anyway), I find it more helpful to have a set of practices for responding to our imperfections — and the impacts they can have on the people around us.

I’ve played with a set of routines at the end of every work day, or sometimes at the end of the work week. It helps me reflect on my day, learn what needs learning, and then let it go. The next day, I feel more free to keep trying, keep learning, keep screwing up, and keep learning some more.

Get Mistakes Out of Your Head

It sounds like your primary need is to regularly get your mistakes out of your head.

When your brain is busy ruminating on mistakes, there tends to be a lot of repetitive focus on what you did wrong or how you are wrong. When you get the information out of your head, you have a better chance of identifying opportunities for repair and self-forgiveness, and any specific learning or behavior change needed as you move forward.

Failure List

I like this tool of naming my “Failure List” at the suggestion of design strategists Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, in their book Designing Your Life.

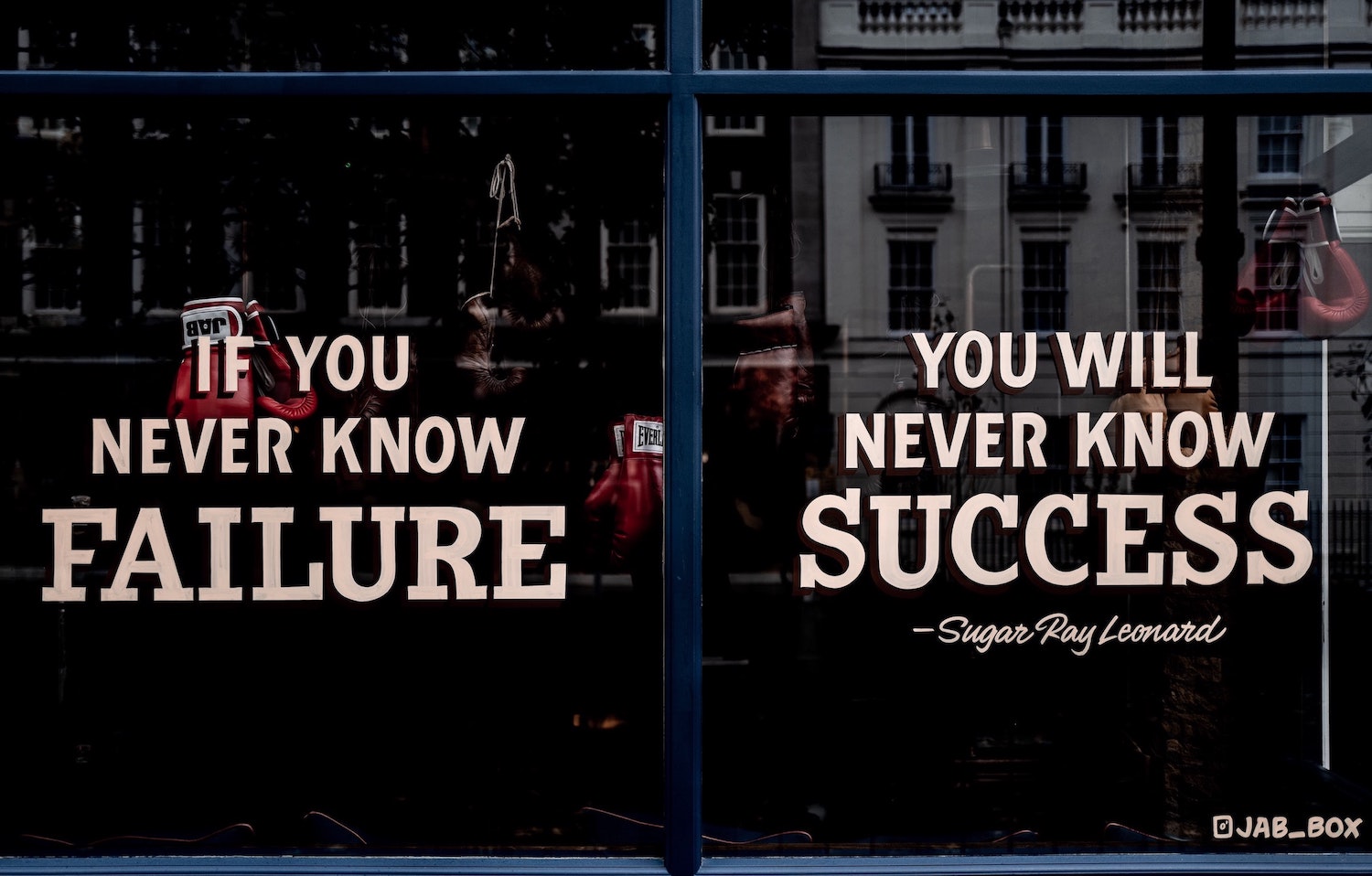

In design, failure isn’t a problem. It’s a known part of how we create and build new things. When we reach failure, we want to identify it as quickly as possible, so we can study it, learn from it, and try again.

I want to note that this kind of design approach works most smoothly on engineering problems when “failure” just means our robot doesn’t work yet. When I work with people and “failure” means that people can be harmed, I want to take some care that I am not just diving into things rushing straight to failure, without any consideration of impact.

And yet … failure is an inevitable part of my work. The Failure List is an opportunity to build “Failure Immunity” — the capacity to tolerate my failures as a place to learn, with humility and grace.

So what is the Failure List?

Make a chart (or borrow this one from the book authors that allows you to log your failure).

The first step is to just log your failure. For me, just naming, “Yep, I messed this up” is a great first step to getting past my perfectionism and just acknowledging that I’ve failed. Once I’ve named that I have failed, I can switch gears to learn from it, offer repairs, and try again. When I get the mistakes out of my head, I often find that I can get more specific about what might need repair or change, rather than continuing to spin through stories of self-shame about how much I did wrong.

The second step is to categorize your failure, understanding how it fits into your patterns of failure and potentials for learning:

- Screwups are things that you usually get right, but messed up this time. You know it was wrong, there’s not much new to learn here. If you’ve caused harm, you might have some apologizing or repair to do before you can move on. An example would be sleeping through an alarm and missing an important meeting, when you’ve never done that before.

- Weaknesses are things that you regularly mess up. You have regularly been trying to improve your knowledge, capacity, and skills here, but you feel at the limit of what will realistically change given who you are and the conditions you are in. Using whatever power or leverage you have, you might strategize how to avoid these situations in the future, or call in other support and resources to fill in what you cannot do. You don’t want to give up on everything as “just a weakness” — but sometimes it’s helpful to accommodate your own significant limitations. An example would be calling in some support to manage your lifelong tendencies to overcommit your schedule and to do list.

- Growth opportunities are things you can learn from, so they don’t have to happen next time. Before you jump into reviewing where you need to repair, you might slow down to learn more about what happened and why. An example would be getting feedback that your latest decision impacted staff in racist and sexist ways.

The next step is to dig in with some learning. What went wrong? What’s important to notice in the external environment or in how you were approaching things? In considering what happened, are you maintaining accountability for any impact or harm you caused? What would you try differently next time?

Make Specific Commitments Toward Repair & Change

While I’ve been enjoying the Failure List, I’ve added a column specifically to track “Repair Work” needed for many of my failures. As noted above, particularly in the kinds of intimate, relational organizing work that I often do, my failures have an impact that cause harm and erode trust. To care for the relationships I’m in, it’s a critical part of my failures to follow-up accountably with any harm I’ve caused.

I know this can sound like a big to do at first. And it’s true that a major harm can include some more significant work. But much of this is about changing daily habits, with how you treat yourself and how you check in with others after you’ve caused harm.

Forgiving Myself

First up: how do you treat yourself when you have caused harm?

I find forgiveness helpful, not to bypass my mistakes, but to give myself a little bit of space to recognize that I am human, and mistakes are part of life.

I reflect to myself on these phrases:

- I forgive myself for any pain and suffering I have caused myself or others due to my own ignorance and confusion.

- I ask forgiveness from all those whose pain and suffering I have caused due to my ignorance and confusion.

- May I take what I learned from today, and use it to benefit all beings.

- May I show love for the world by loving myself, just as I am, even the messy parts.

- May I take in this learning, and continue to show up happy and free.

When forgiveness feels like too much of a stretch, I set the intention, “May I be able to forgive myself for these mistakes in the future. And may others someday be able to consider forgiveness for my mistakes.”

Repair: Who needs an apology, and how?

If I have harmed someone specifically, there’s work to do to repair that relationship. After learning more about what happened and why, a direct apology can be a fundamental step in rebuilding trust.

Mia Mingus writes about How to Give a Good Apology (parts 1 and 2), sharing learnings from the Apology Lab designed by the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective.

“Apologizing is a chance to acknowledge and take responsibility for the hurt or harm you caused or were complicit in. It is a moment to demonstrate to those you have harmed that you understand what you did and what the impact was.” – Mia Mingus

When we develop our capacity to apologize, it becomes an integral part of our relationships. We want to tend to the hurt. We want the other person we care about to know that we are listening and seeking to understand their view of reality.

“Apologizing is part of accountability and accountability is a sacred practice of love. If you’ve hurt someone you care about, it is sacred work to tend to that hurt. You are caring for this person, the relationship you share, as well as your self. You are engaging in the sacred work of accountability, healing, and being in right relationship. This work is part of the broader legacy of transformative justice, love, and interdependence. Do not take it lightly and give it the respect it deserves.” – Mia Mingus

Repair: What will I learn or practice for next time?

As you reflect, you can summarize any next steps that remain:

- What do you still need to learn or study, and where might you find good resources?

- What do you need to practice, and how can you get some regular exercises in?

- What do you want to remember to try differently, next time a similar situation comes up?

- Who might you call in for support or guidance?

I know these feel like additions to your already long to-do list. But they are long-term investments in your capacity to be in good working relationship, so they offer some long-term changes that are worth the investment. In permaculture style, see how they might “stack” onto other work you already need to do. For instance, you might add a mentoring related question about apologizing to coworkers to a meeting you already have with someone whose relational skills you really trust. Or you might practice saying your forgiveness phrases to yourself every time you use the restroom between meetings.

As I am learning, repairing, and growing, it helps me to remember: Some situations are just hard. When I am building a new world, I don’t have any guidance or blueprints to follow, so large and small mistakes are part of the process. There is no magic self care that will make this situation easy. Keep breathing. Relax into greater wisdom.

With love,

The Resourceress

Photo by the blowup on Unsplash

Leave a Reply